A Conference About Software You Can Love

This October I’m going to host “Software You Can Love” (SYCL, pronounced “cycle”), an in-person conference about the art of creating software for humans. If that sounds interesting already, you can find information about the location and ticket prices on the official website.

What does SYCL mean?

Software you can love is software whose main goal is to serve the end user, and it’s alarming how rarely we get to deliver this kind of software professionally. I believe I’m not alone in saying that there’s pride and pleasure in creating software that others want to use because it solves a problem with elegance, so the big question is: how can we make more of that?

Conferences are financial ventures and their nature makes them extremely susceptible to hype cycles, but ultimately they exist to stimulate and disseminate ideas. You might be someone who doesn’t go to conferences, but we all have learned at least something from a talk given at a conference held somewhere. And yet, while conferences can be a useful tool, I don’t think the answer to the big question lies in microservices or any of the popular conference topics.

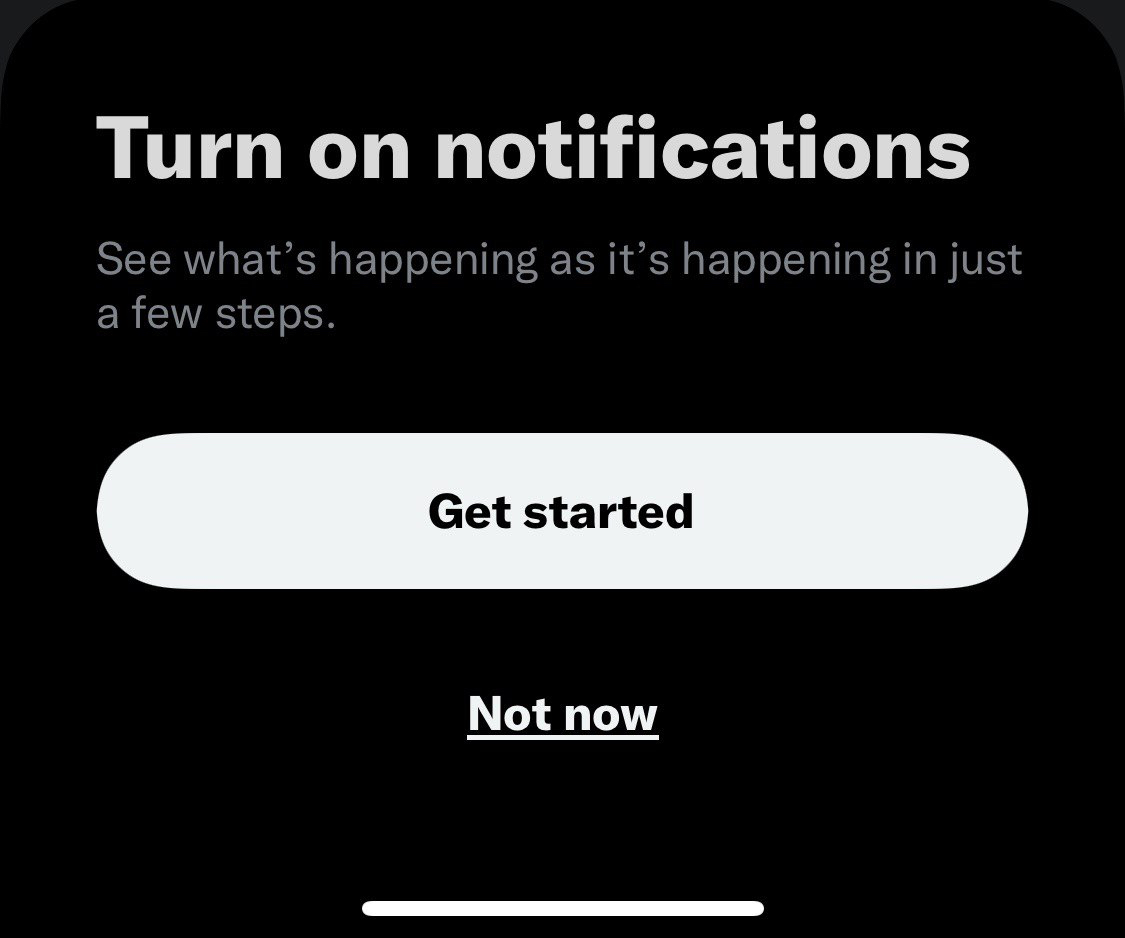

Sure, the problem of unlovable software is in good part technical in nature, but for example there’s no technical limitation that forces the Twitter app to constantly ask me to enable notifications, with no way to permanently say no.

I want SYCL to be a conference that tackles the problem of how to make more software you can love on all levels of abstraction: from technical topics, to understanding how business models impact software. Accepting a wide range of talk topics is nothing new, but I’d like to stress once more that every topic of discussion is meant to inform our answer to the big question of how to create more software you can love.

This means that I will (probably) not accept talks about microservices not because I hate the practice or want to be a contrarian, but simply because I don’t believe that more “monoliths vs microservices” discussions are going to make software significantly more lovable. Conversely, I would be more interested in a talk about how to improve native application toolchains, so that we can stop shipping Electron apps.

This last point is particularly relevant because the second question that I want to prioritize is how to make creating elegant solutions more enjoyable, so that we can improve our own experience as software developers. I don’t believe in martyrdom, and so I don’t expect anybody to become a human sacrifice in the name of making somebody else happy. This means that I don’t blame developers that ship Electron applications because I know how convenient it can be.

That said, I would love for my desktop applications to be more conservative with resources and visually more consistent with the OS than what Electron allows, and I believe the only realistic way to achieve that goal is to make native development more compelling for the developer.

Software that serves the end user… isn’t that Free and Open Source Software?

I wish. Maybe it used to be, but I don’t see modern FOSS as embodying these values anymore.

In the beginning Open Source was just a thing people did in their free time, so big tech didn’t really care about it, but over time it became an unavoidable aspect of doing business. Want to build a new database or dev tool? Good luck getting any traction if it’s not Open Source. And so big tech adapted and learned how to deal with the problem, to the point that Open Source is often used to implement a form of kayfabe, layered on top of a very dry set of rules for licensing software.

This is not to say that everything that brands itself as Open Source is bad of course, far from it, but “Software You Can Love” is an expression that I’ve created explicitly to avoid feeding a brand that twists spontaneous collaboration into becoming a smokescreen for big tech’s fight for dominance.

In Playing the Open Source Game I’ve talked at length about my experience with Open Source, but I elected to avoid spending words on the Free Software movement in it, which instead I’m going to do now.

At its core, Free Software is a reasonable idea: the end user should be able to inspect, modify and redistribute the software they use. In practice most people don’t know how nor care about reading the code of most programs they use, but I really wish that was the biggest problem with Free Software.

What I find appalling about the Free Software movement, is how tragicomically ineffective its leadership has been over the years. About one month ago Richard Stallman held “The state of the Free Software movement” and really gave a good display of the quality of their advocacy work: first he complained about Ubuntu not being free enough, then pointed out that it’s ethically wrong to play non-free online videogames, and finally announced a new GNU C manual.

It’s unacceptable to me how nonchalantly you are being asked to make sacrifices (never use any proprietary software ever!) by people who think that a new GNU C manual is exactly what we need to improve the state of software. Users need to be protected from hostile design, but the solution is not retreating to a free software monastery to study the (GNU C manual) book.

In conclusion

If you too think that there’s an important quality often missing from both proprietary software and modern FOSS, then join us this October for the first ever SYCL in-person event.

For the sake of clarity, SYCL is not a user experience conference. UX is in scope, but far from being the only focus. Going back to the Twitter app example, a product manager greenlit the design decision to make it impossible to permanently turn off the popup. In all likelihood, that product manager knew perfectly well that it’s a dark pattern, which means that discussions about UX are not enough to push back against this kind of behavior.

Above I described software you can love as software whose main goal is to serve the end user, but I don’t believe this description to be complete. There’s more to software you can love and I’m hoping for the conference to help us discover and articulate what else is missing, so If you have a story to share about what in your opinion is (or isn’t) software you can love, there’s an open Call for Speakers.

This first year we’ll also have a full day of Zig talks. This is done partially for practical reasons, and partially because I want the Zig community to focus on what’s really important: making sure that your software has a positive impact on your users, and that you enjoy creating it.