I Want Simple, Not Just Easy

Simple → Complex is the dimension that describes how irregular and interconnected a system is. Simple systems can be broken down into smaller pieces that are understandable in isolation. If you make changes to one of those pieces, you don’t have to fear unexpected ramifications in parts not directly connected to what you’re operating on. Complex systems are the exact opposite: you’ll need to keep in mind a lot of things and tread carefully.

Easy → Hard is the dimension of how much energy and time it takes to successfully execute something. Easy things generally require less preparation and can be done reliably even by inexperienced individuals. By definition, hard stuff requires more effort and not everybody gets it right all the time.

It goes without saying that complex things tend to be hard, while simple things tend to be easy, but that’s not always the case. Software engineering can shift this balance almost alchemically, although not always for the best.

Building abstractions

Every time you build an abstraction, you encapsulate a given amount of complexity, making it easier to use. When you print to a terminal, you’re probably doing it in a single line of code: that’s an abstraction over a whole lot of subsystems that you might not even know about. It’s easier to print that way, but the complexity is still there, hidden behind a single function call.

So what’s the point of abstracting?

While in the previous example abstracting did not decrease complexity, it did draw a box around a subsystem. If you remember, simple systems are made up of smaller boxes, so abstraction is a step towards composing bigger systems without increasing complexity too much. It’s also good that it made things easier: if it took 100 lines of code to print something to a terminal, we would be years behind compared to where we are today, just because of all the economic implications.

This is why we don’t write everything in assembly. It’s easier (more economical) to write in higher-level languages, and function calls, for loops and other flow control structures proved to be good abstractions over machine-level operations. Keep in mind: none of these things further simplifies assembly code, but they do actively prevent it from exploding in terms of complexity, as it would easily do without small boxes such as functions, etc.

Not all abstraction manages complexity

Abstraction is sometimes introduced just to make things easier. An example would be when you’re introducing a new interface with the sole goal of making it easier to swap in and out a replacement for a component. It will take you less effort to make that specific change (fewer references to update), but the box that you just drew is a second layer around a pre-existing block (the concrete class). Think for example about Database (class) and IDatabase (interface). That interface is only useful for swapping in a new database. If it were a way of abstracting what the class does, it would have had a different name to begin with.

Easy is better than hard

All else being equal, there is no reason to prefer hard over easy. Stealing a quote from Economics, we have an infinite amount of things we could learn or build, and an ever limited amount of time and energy to do it. The cheaper we can do it for, the more we can have, and the benefits compound over time. It’s a bit of a trivial statement, but I want to make it clear before diving into the real issue.

The rules of abstraction

As I mentioned before, introducing abstraction has two main effects:

- Lowers difficulty by hiding some of the details. Fewer lines to write, fewer things to keep in mind and think about — or even to right out know.

- Identifies a cohesive subsystem and draws a box around it. The box becomes then a tool that can be reused to build bigger systems, while keeping complexity down.

The second point, complexity management, is not trivial. It’s easier to lower difficulty rather than constrain complexity, and that’s often what happens when development is blind to this concept: easy software that encapsulates more complexity than it should.

Easy complexity

Easy complexity shows up in many places, causing all kinds of problems. We even have a friendly name for some incarnations of easy complexity: bloat. Saying that something is bloated is sometimes taken as a generic complaint against a misunderstood technology, and certainly the term gets abused, but it’s nevertheless a legitimate way of describing something that fails to manage complexity in a misguided effort to make things easy.

Using bloated tools

The universal property of bloated tools is being resource-hungry and needlessly slow. In the beginning, this seems almost innocuous, but as time goes on you will find that a significant percentage of human and system time gets wasted on waiting for them to perform even trivial operations. When something breaks or behaves strangely, there is no way of knowing what exactly went wrong and why. Developers that over-rely on this type of tool get progressively caught in a form of lock-in where the tool removes them from the details of what they are doing (“the tool does it for me”), making them more productive, but at an unfair price. The lock-in is not just in terms of technology: when you only approximately know one way of doing things, you will also be limited in the range of things you can do, because every small deviation from the tool-sanctioned way will become a serious obstacle.

The self-preserving structure of these problems is nothing short of amazing. Maybe in the beginning the developer tried to investigate root causes and different ways of doing things, but failure after failure, it’s reasonable of them — although ultimately wrong — to conclude that this approach is just a waste of time. At that point some decide that the right solution is to double down on learning how to cope with the tool’s quirks and intricacies, which will result in even more wasted time once a new shiny tool comes along.

Of all the forces at play in software engineering, this is one of the strongest forms of natural selection: choosing slow and unreliable tools will make you a slow, unreliable developer with a limited and quickly depreciating skill set. It’s harsh, I know, but true. Choosing better tools won’t make you necessarily a good developer, but when you can understand what you’re doing, troubleshoot problems, and in general be able to iterate quickly, then you will have a real opportunity for improvement.

Not all bloat is evil

I’m purposely avoiding naming names, but I’d like to give a positive shoutout to JavaScript. We all equate JS with bloat, but in my opinion what happens there is mostly the natural result of a healthy ecosystem where many different (although sometimes half-baked) abstractions compete against each other. This still has the negative effect of making it harder to make sense of things, and causes some developers to experience burnout, but the number of broken developers (as per description above) that the JS ecosystem creates is not proportional to our perception of its bloat-ness. I think the biggest number of that type of developers comes from different ecosystems where bloat is the result of hostile design, but that’s a story for another blog post.

In Conclusion

Using bloated toolchains will have negative effects on both your productivity and personal growth. Slowness alone is a problem, but when combined with unreliability, it becomes devastating. Think about this the next time you see somebody open their IDE, wait for it to load, make a change, and then have to wait before the red underline caused by their changes disappears, plus the occasional crash. A reliable environment is a fundamental prerequisite for building competence. The second most important prerequisite is a feedback loop that allows you to quickly gauge the result of your actions. The tighter the feedback loop, the better. When it takes minutes to build a project and run a fistful of tests, the loop is definitely not as tight as it should be.

Using bloated frameworks will prevent you from understanding the details of what you’re doing and cause your software to inherit bad traits such as slowness and unreliability, further spreading the effects of easy complexity. New approaches will inevitably come, and if you never built an appreciation for the different trade-offs, all change will seem useless and arbitrary.

The economy of complexity

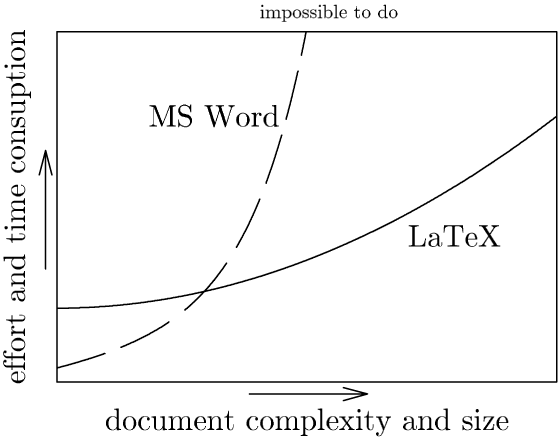

If you search “word vs latex” in google images, you will find a few pictures similar to the following:

This picture is trying to convey that, while Microsoft Word is easier to use than LaTeX, as document size increases, you will quickly get to a point where it actually becomes easier to use LaTeX, despite the inverse being true initially. Complexity makes things hard and Word fails at containing it, causing difficulty to skyrocket. This is why you can’t ignore complexity. It doesn’t matter how easy you try to make things: complexity is an almost radioactive source of difficulty.

In terms of value over time, if your daily job involves working on big and complex documents, learning LaTeX is going to pay off immensely compared to sticking with Word. More importantly, learning the idea of giving semantic structure to documents is going to pay off more than learning that one arcane procedure required to drag & drop pictures without messing up the layout in Word. Once you begin appreciating the relationship between structure and semantic meaning, you won’t feel bad when something new comes along and starts replacing LaTeX, because the fundamental principles will transfer to the new tool, while the image placement incantation for Word is probably going to stop working in the subsequent release, leaving you with nothing.

I leave it to you to decide if and how that picture translates into toolchains, frameworks, and even the software you write yourself, but there is an old saying that I think is still as valid as ever. I don’t remember the precise quote, but it’s something along the lines of:

The value of a maker is reflected in the quality of their tools.

Thanks for reading my first blog post!

My next post will probably be about a new programming language called Zig and some considerations that popped into my mind when using it, but I’m not done complaining about complexity yet. Not all easy complexity is bloat, some takes a different form that definitely deserves a dedicated post, and I didn’t touch on the subject of what it takes to actively simplify a system. And there’s also the hostile design thing…