The Python Package Index Should Get Rid Of Its Training Wheels

As somebody directly involved with an upcoming programming language, I’m often in discussions about how to model things in the ecosystem like, say, the package manager, and how those decisions impact the project in the long term.

When reading Simon Willison’s excellent blog post “Things I’ve learned serving on the board of the Python Software Foundation” (which I recommend reading it before continuing), the part about PyPI (Python Package Index) stood out:

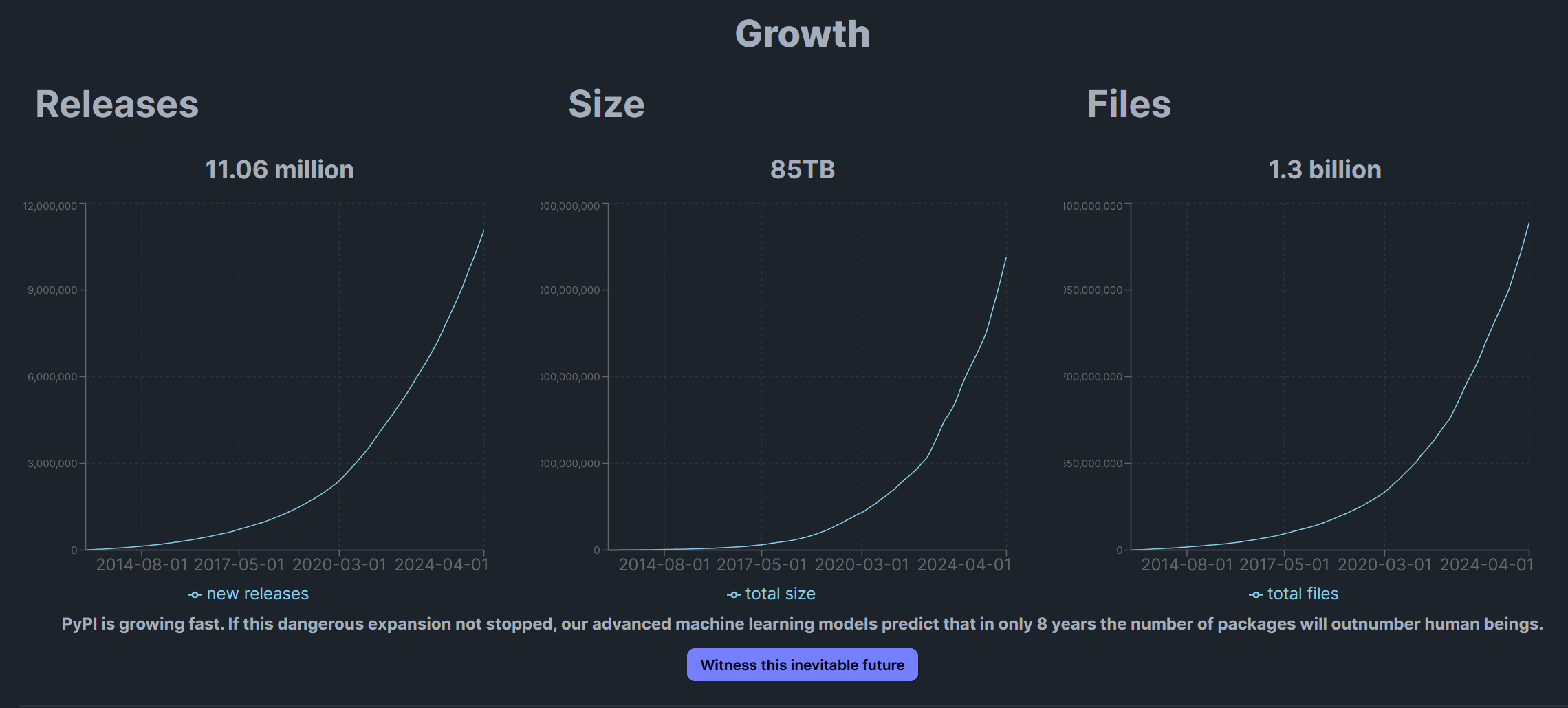

PyPI’s numbers are staggering. Today there are 570,000 projects consisting of 12,035,133 files, serving 1.9 billion downloads a day (that number from PyPI Stats). Bandwidth for these downloads is donated by Fastly, a PSF Visionary Sponsor who recently signed a five year agreement to continue this service.

(This was a big deal—prior to that agreement there was concern over what would happen if Fastly ever decided to end that sponsorship.)

Emphasis mine. It would indeed be hard to survive without that kind of support from a corporation. A user on HN estimated the yearly cost of this traffic at around 12 million USD/year (according to AWS Cloudfront rates), more than four times the full operating budget of the Python Software Foundation as of 2024.

We saw the beginnings of this in the Zig project and immediately moved to a self-hosted solution but I want to focus on PyPI in this post, so let’s try to imagine a contingency plan for if/when no corporation is going to offer free credits to the Python project anymore.

Before I begin, I want to make it extremely clear that I’m not involved with the PSF, nor PyPI, and that I’m talking as an external person with only partial knowledge of the facts. I’m the dark knight nobody asked for.

What if PyPI had to pay its own bills?

To answer this question, we need first to get a rough idea of how PyPI works.

PyPI hosts packages for the Python ecosystem. A Python package can contain both source code and prebuilt binaries. The source code is usually Python code, while the binary part is usually prebuilt C/C++ code.

One of Python’s greatest accomplishments has been democratizing access to C/C++ projects, but that has the implication that the Python ecosystem has a strong dependency on an ecosystem that it doesn’t control. One full of problems and intricacies.

Building C/C++ projects is usually extremely complicated and brittle, and so the Python ecosystem assumes that it’s unwise to expect a build to succeed on user machines. To solve this problem, package authors have the option of creating prebuilt versions of their native dependencies and upload them to PyPI in the form of Python Wheels.

Prebuilding binaries solves completely any kind of build issue, but it has its own set of downsides. I gave a talk at PyConIT where I went more into detail of what those are.

For the purpose of this blog post, the main problem to keep in mind is that prebuilding binaries causes an exponential growth of the amount of data PyPI has to store.

The reason for the exponential nature of that growth is simple: prebuilt binaries must be created for every combination of CPU architecture, OS, and sometimes also other things, like interpreter version.

Just to give you an idea, you need to build for: arm-linux (some embedded boards), arm-windows (some other embedded boards), aarch64-linux, aarch64-macos, aarch64-windows, x86_64-linux, x86_64-macos, x86_64-windows.

As the bare minimum, and this has to happen for every release of your package! The list is not fixed in stone, and some combinations are going away (like x86_64-macos), but the list is overall getting longer, not shorter (e.g. RISCV).

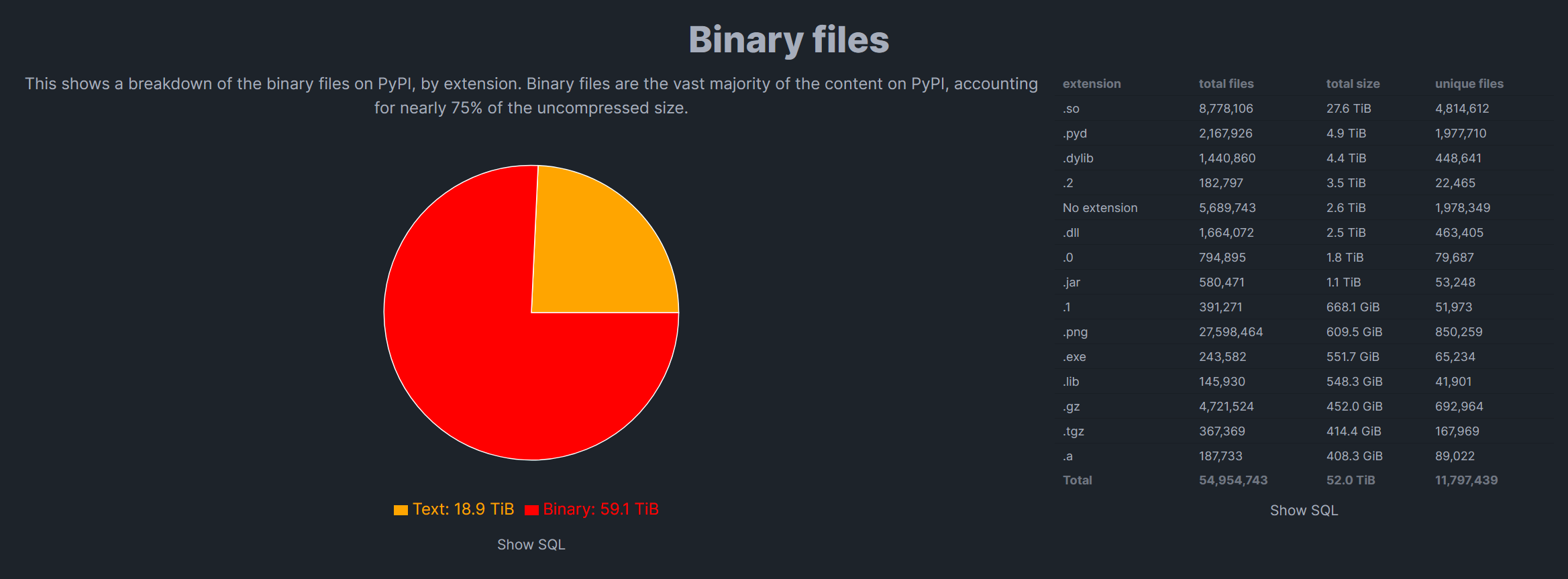

If you look at some PyPI stats, you will see that PyPI is indeed growing exponentially and that most of the occupied space is prebuilt executables (the red part of the pie chart, representing 75% of the total space).

The site even added a funny “Witness this inevitable future” button to extrapolate on the growth curve. But the button is wrong, this future is far from inevitable, and the only thing Python needs is a clear strategical vision.

The main issue with the current situation is that the binary data is both extremely redundant and irreplaceable at the same time.

We just talked about its redundant nature, while what makes it irreplaceable is the fact that if you were to lose some prebuilt binaries, the system would not know how to reconstruct them, thus leaving the package in a broken state.

While there might be some best practices for Python package authors (probably mostly centered around profuse use of containers), as far as I’m aware, each project is left to its own devices when it comes to figuring out a way of creating prebuilt binaries.

It made total sense in the past for the Python ecosystem to be hands-off when it comes to building C/C++ code, but it’s now time to take the training wheels off instead.

Taking the training wheels off

Here’s finally my contingency plan for PyPI:

- Leverage progress in the systems programming ecosystem to create repeatable builds.

- Turn prebuilt binaries from “sources” into cacheable artifacts that can be deleted and reconstructed at will.

- Institute a way of creating secondary caches that can start shouldering some of the workload.

1. Leverage progress in the systems programming ecosystem

When Python came into existence, repeatable builds (i.e. not yet reproducible, but at least correctly functioning on more than one machine) were a pipe dream. Building C/C++ projects reliably has been an intractable problem for a long time, but that’s not true anymore.

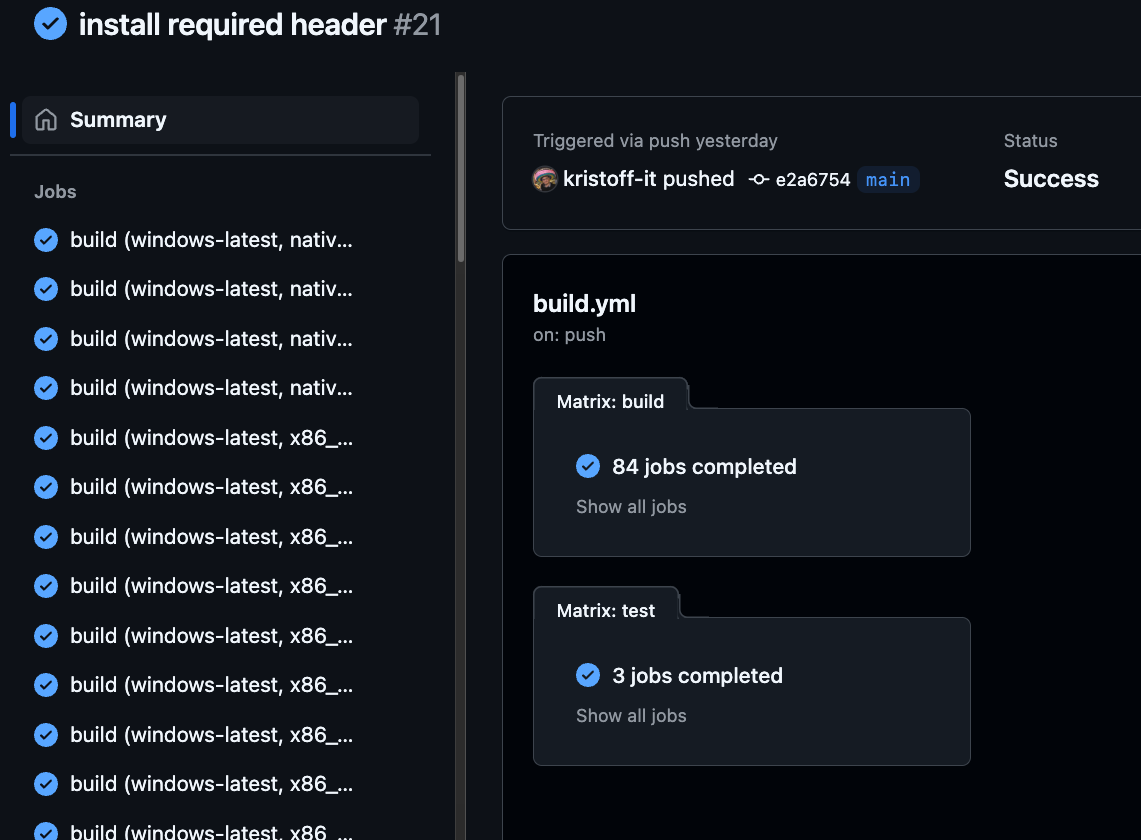

The Zig build system can trivially compile C/C++/Zig from any target to any target. To give you an idea, I’ve created https://github.com/allyourcodebase (will blog about it properly soon, promise) where Zig community members create Zig build scripts for existing C/C++ projects.

Here you can see an example CI script that literally builds from every combination of host machine, to any combination of target machine, each build succeeding simply by running zig build with the appropriate target argument. Go to the Actions tab to see the job matrix generate a long list of successful builds.

Even the Rust ecosystem has started using Zig whenever cross-compilation becomes a concern (e.g. deploying on AWS Lambda), using cargo-zigbuild.

Python package authors can already create packages that depend on the Zig compiler in their installation phase because the Zig compiler is available on PyPI, meaning that the user doesn’t need to have installed it manually beforehand.

To be clear, somebody must still put in the blood and tears required to package correctly a given C/C++ project but, once that’s done, the result can be reliably repeated with a single command from any host for any target.

Containers barely give you the “from any host” part.

A while ago I went on Developer Voices to talk about the Zig build system (I did also talk about Python as a specific example):

2. Make prebuilt executables optional

Once the Python ecosystem can trivially rebuild binaries for any target, then PyPI will gain the ability to delete (and recreate) wheels at will.

This will free a lot of space. Think of all the patch releases from old versions of a package that nobody cares about anymore.

Additionally, PyPI will be able to serve more source code, and fewer prebuilt binaries (since now source distributions can be reliably be built by users), which will put a dent into the yearly total data transfer, if coupled with a good compression algorithm (in my experience source code compresses better than binary data).

That said, not every project should get rid of prebuilt binaries. Building LLVM takes half an hour on a decent machine, for example, so it’s definitely worth caching it.

PyPI will have the option to cache big and/or hugely popular packages if it needs to, which brings me to the final step of this whole plan.

3. Institute secondary caches

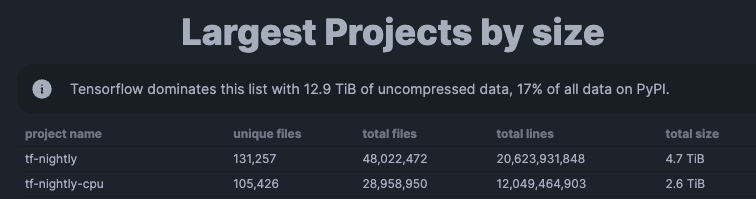

Looking at some more PyPI stats, it seems that space usage across different projects follows a pareto distribution, having Tensorflow lead the charge by singlehandedly accounting for 17% of the total data.

It would be nice if projects like Tensorflow were given a chance to shoulder their own weight, so to speak. This could be done by implementing a way for a package to optionally declare a secondary cache location where to find prebuilt binaries.

Here’s one way it could work:

- As a package is added to PyPI, it gets built for every target it supports.

- PyPI adds to the package metadata the hash value of each build.

- Secondary caches download from PyPI a copy of each build, acting as mirrors.

- When a client wants to install a package, it can download the data from a secondary cache, if PyPI decides to delete the original builds.

- The client can use the hash metadata to validate that the downloaded data is what it expects.

Note how by treating secondary caches as mirrors, you don’t even need reproducible builds, which is a nice property, as some C/C++ projects might be particularly resistant to being made fully reproducible, although that’s an improvement that could definitely be pursued after an initial solution is in place.

Of all measures, this is the one that would make the biggest difference in terms of bandwidth consumption. It also has the beautiful property that it redirects costs in perfect proportion to how many resources a project consumes, and that it leaves to PyPI the latitude to choose a case-by-case policy that creates the best structure of incentives.

In conclusion

Simon Willison is absolutely right that big ecosystems require strategical thinking. Without a concrete effort by power structures to steer the community towards a promising point on the horizon, all that remains are short term incentives, partial information, and a lot of space for actors with hidden agendas to grease the wheels gears they like the most.

Python could very well continue relying on the support of the Big Tech industry for a very long time but, even if we were to set aside the otherwise extremely real problems of power dynamics between organizations, the long-term sustainability of an exponentially growing dataset still remains and Python is now mature enough to start inspecting and fixing the foundations its ecosystem is built upon.

At the Zig Software Foundation we look up to the Python Software Foundation as a great example of a fellow 501(c)(3) non-profit organization that was able to grow an incredibly vibrant community, and we sincerely hope that Python will find a way forward that increases computational efficiency and keeps the ecosystem as independent as possible, regardless of the technical details of how that outcome is achieved.